‘He could do more things better than any player I have ever seen. He was a magnificent distributer of a ball, he could beat a man on either side using methods that no one had ever thought about, he could shoot, he could tackle, he was competitive and yet cool under pressure. What more could you want? I mean what is the perfect player? Two good feet? The kid had them. Strong in the air? He could beat men twice his size. Ability to score goals? Only Greavsie and Law have equalled him and I think his ability to score a goal out of nothing was even greater that theirs. Courage? I’ve never seen a braver player. He could play at the back, in midfield or anywhere up front. He was probably the best bloody keeper at the club too, but we never tried him!’

‘He could do more things better than any player I have ever seen. He was a magnificent distributer of a ball, he could beat a man on either side using methods that no one had ever thought about, he could shoot, he could tackle, he was competitive and yet cool under pressure. What more could you want? I mean what is the perfect player? Two good feet? The kid had them. Strong in the air? He could beat men twice his size. Ability to score goals? Only Greavsie and Law have equalled him and I think his ability to score a goal out of nothing was even greater that theirs. Courage? I’ve never seen a braver player. He could play at the back, in midfield or anywhere up front. He was probably the best bloody keeper at the club too, but we never tried him!’

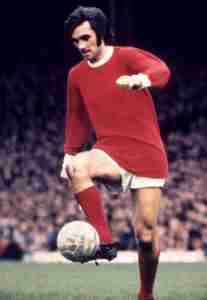

– Paddy Crerand on his teammate George Best, as quoted in ‘Best: An Intimate Biography’ by Michael Parkinson (1975)

It was the mid-1980s, and I was behind the counter in our family pub in the centre of Rooskey village. The mornings were busy, with workers from Hanley’s factory taking breaks. The afternoons were less predictable.

On a good afternoon, there might be five or six characters in, the conversation a fascinating mix of gossip, banter, mischief and…fake news. On quieter days, the young barman (yours truly) might be trapped with the dreaded…lone customer. There are only so many times you can reference the weather, and the objectionable price of a pint.

Still, they were good times. There was one man who seemed old to me, but looking back, he may only have been in his 50s! He often fell into the ‘lone customer’ slot, popping into the village for a few afternoon drinks.

I liked him. He was intelligent, softly spoken, a bit of a dreamer, but cursed a touch by drink and loneliness. I always felt, when chatting to him, that he had to be dragged away from the grip of melancholy. He’d been in England for years, and now, like many of the men who frequented the pub, he was inclined towards sentimental speeches, what might have beens.

When I’d suggest that it must have been wonderful to be in London in the 1960s, he returned there in his mind, but before he could embrace any happy memories, a slumbering sadness took over…a lament at the passage of time perhaps, or for a romance that might have been.

One day we got talking about the soccer in the 1960s, and I asked if he’d gone to any games during his years in England. His eyes came to life. We talked a little more, then I asked about George Best.

“George Best” he exclaimed gently, savouring the magic of the words. “Ah…George…Best”.

I waited and watched as he closed his eyes and went back in time. Because he was a dreamer. Then he looked at me.

“When George Best came to London, the crowds came out. It didn’t matter who you supported, the stadiums were bulging when he was playing. I used to go to lots of games, I saw all the top teams, all the top players. But when George Best came to London, we’d seen nothing like it. Any time he came to play, we went to get a look. He was magic”.

He cradled his whiskey glass and closed his eyes again.

“Ah, when George Best went down the wing…” And he smiled and smiled…and there was nothing I or the redundant melancholy could do to break this beautiful spell, the joys of yesterday.

By the time I became aware of George – and what a discovery that was – the genius was fading. It was the late 1970s, and the ‘Belfast Boy’ was on tour, a self-destruct one at that.

He’d left Manchester United in 1974 at the age of just 27, frustrated by a great team’s decline – and seemingly having fallen out of love with football. He was also in decline himself, just when he really should have been peaking. By then, Best was living an undisciplined and somewhat reckless life, his nights on the town beginning to take their toll on his health, his fitness and his performances on the pitch. He was still a great player, but he was burning the proverbial candle at both ends. That’s probably putting it kindly; ‘self-destructing’ perhaps sums up this phase of Best’s life more accurately.

Best became a shadow of the player who, at his peak, was arguably the world’s best footballer. ‘Touring George’ played for a number of clubs around the world, a fairly bizarre list, it must be said. He had some success in America, where he was a high profile recruit (he scored a wonder-goal for San Jose Earthquakes which you can enjoy on YouTube). A period with Fulham was marked by flashes of the old magic, as an overweight Best partnered with soul-mate Rodney Marsh. There were less successful stints with Hibs in Scotland, Dunstable United, Cork Celtic and Stockport United. But that is quite enough from me on Best’s decline! Because, before the fall, there was a career of such brilliance and magnetism – such sheer genius – that it places George Best in the company of Pele, Maradona, Messi and a handful of other footballing Gods.

By the time I became aware of George, his best days may have been behind him, but he was still playing, still hypnotic. I quickly went about discovering everything I could about the man. I consumed the books, the videos and documentaries. And I soon discovered that the scout (Bob Bishop) who sent a 15-year-old George Best to Manchester United was right when he told the club manager Matt Busby – “I think I’ve found you a genius”.

Best made his Manchester United debut when he was 17 – and soon the whole world was taking notice. Quickly it became apparent that this was an extraordinarily gifted footballer. A winger, he ravaged the best full-backs in the country. After Best had destroyed Chelsea’s highly-rated Ken Shellito, George’s teammate Paddy Crerard memorably quipped: “Shellito was taken off, suffering from twisted blood”.

Best will always be revered by fans, not just because of his brilliance as a player, but because of the joy he gave. He was a showman. Occasionally he taunted opponents, inviting them to tackle, invariably eluding them when they dived in. Often he humiliated defenders, beating them a second time in the same dribble. Some of his goals are amongst the most celebrated in the history of the English game. I advise readers to look them up on YouTube. There’s a stunning solo goal against Spurs; two famous goals against Benfica in a European Cup semi-final on a night which catapulted Best to superstardom; his decisive goal against the same opposition in the 1968 European Cup Final; another, an outrageous, measured, ludicriously audacious chip over several defenders and goalkeeper; six goals in an FA Cup game (v Northampton), and any amount of other marvellous solo efforts following mesmerising dribbles.

Loving Best was easy – not only did he have ALL the skills, he actually introduced new ways of beating defenders. Some of his dribbling techniques had never been seen before, and could not be replicated. I also loved him because of his great courage. He took ferocious abuse from the hardmen of his era, great men like Tommy Smith, Norman Hunter and Chelsea’s ‘Chopper’ Harris. Best had amazing balance, and frequently he somehow danced away when these formidable men tried with all their might to fell the genius who threatened to torment them. He was also an excellent tackler, and a superb header of the ball! Best won two leagues and a European Cup with Manchester United, and was European footballer of the year in 1968.

‘For five years, from the beginning of 1966 to the end of 1970, he was comprehensively better than the rest – the most accomplished player on God’s earth. The lucky ones, who has seen him from the cramped terraces of Old Trafford and Windsor Park, boasted of the fact and sympathised with those who, through the unfortunate circumstance of not being born soon enough, were deprived of the privilege and had only glimpsed him second-hand on grainy monochrome or early colour film. They spoke of a variety of treasured goals scored from near impossible angles or spun out of the least promising thread – dinks as gentle as a caress and shots of rippling power. They spoke reverentially of skills that were supernatural and which stirred the spirit, gloriously precocious labyrinthine runs that began on the half-way line and increased in pace the further he travelled. They spoke of poise and balletic balance, classified as being otherworldly. They spoke also of a fabulous tensile strength that enable his willowy body to survive challenges that, if committed outside the marked perimeter of a football field, would have counted as common assault or grievous bodily harm. He was the complete player’

– From ‘George Best: Immortal’ by Duncan Hamilton (2014)

Having found him, I never let him go. In 1982, I was beside myself with excitement when there was speculation that Northern Ireland manager Billy Bingham might include the veteran Best in his panel for the World Cup. I was devastated when it didn’t happen.

He finally retired in 1984, after electrifying the world with his magic. Ravaged by alcoholism, George Best died in 2005, aged just 59. Back in Rooskey, the nice man who wasn’t old died when he wasn’t old. He liked a drink too. Melancholy was his partner to the end. He had his good days too, and he purred wirh dreamy nostalgia that day I asked him about George Best.

That’s George Best, the sometimes troubled genius. Unforgettable. Unstoppable. He will always be celebrated as one of the greatest and most entertaining footballers of all time. Go to YouTube now!